E___cruciating E___perience

Theodore Monk

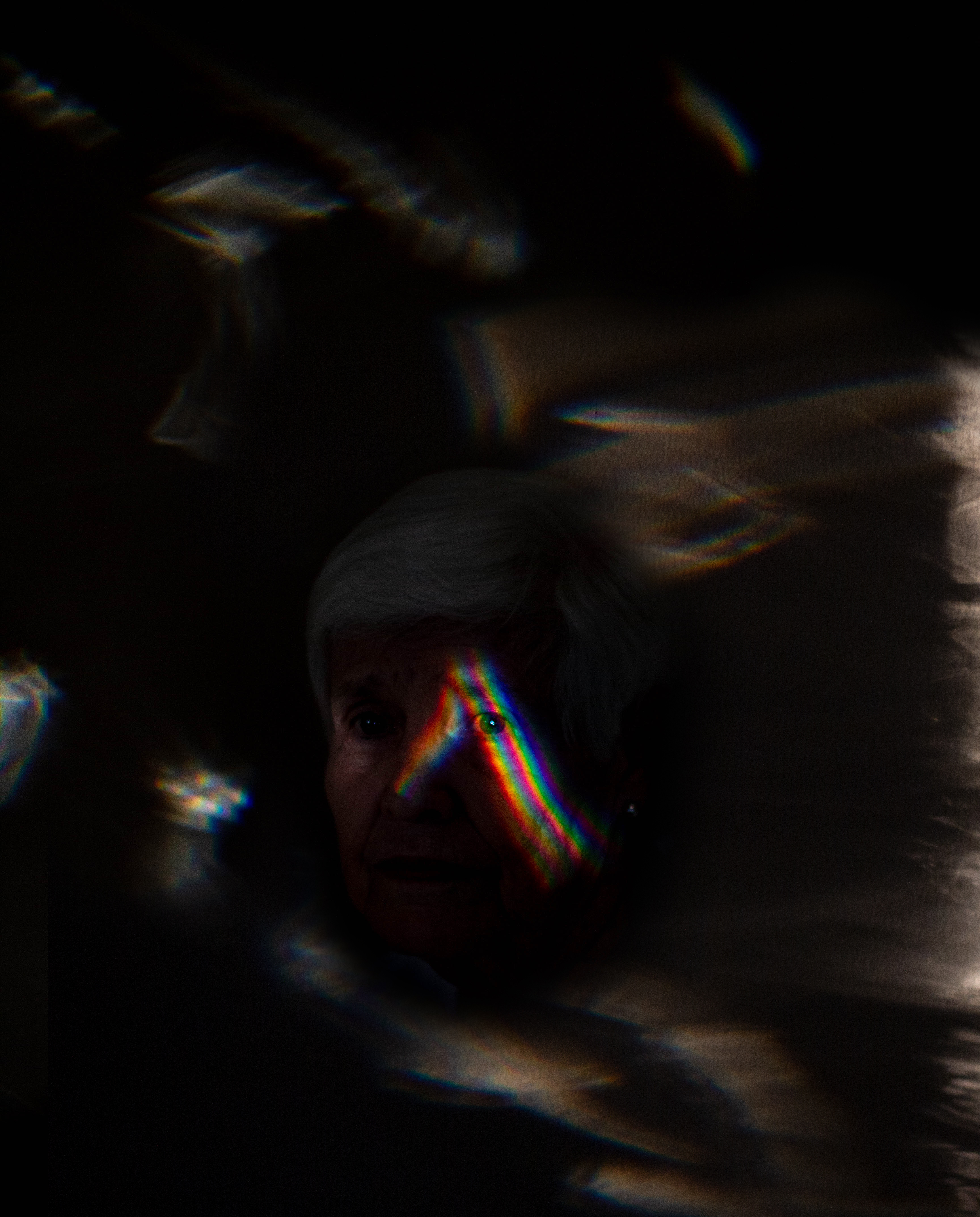

Dual Reality | Sarah Westmoreland | Photography

Under a dark and dreary mid-morning sky, the children are heralded to the woods. The trees stretch forever in both directions, surely ending somewhere, but not anywhere the children have ever seen.

The children are accompanied by their parents, but the parents are not allowed to enter the woods with them. That would be cheating.

Everyone, children and parents alike, freezes at the dense border of trees, eyes wide with poorly-concealed fear. This year, at the back, a child can be heard wailing in terror, his father desperately trying to calm him as he gazes at the black-robed men surrounding them; first he shushes, then he pleads, and finally he puts both hands over the boy’s mouth and pushes him into the dirt, tears in his eyes as the muffled screaming goes quiet.

It is no matter. It is time to begin. “Welcome, dear children!” comes the voice, the voice from deep within the woods, “Welcome, one and all! My, but how some of you have grown! Is—is that—is that you, little Monica Peters?” Near the front of the crowd, a little girl with ragged brown hair feels her heart skip a beat. She nods, answers as she feels a sharp push from her mother, “Y-yes.”

“Why-hy-hy,” the voice chuckles, “You must have grown by a yard since we all last saw you! You put your spoils to good use, no?”

The girl named Monica Peters nods, giving as unmirthful a laugh as had ever been heard. “Y-yes, sir,” she says, as she’d always been taught, “Thank you so much for your kindness.”

“And thank you, darling,” the voice says, “But I’ve spent enough time reminiscing. You’re all dying to get started with this year’s hunt, aren’t you?”

The children and the parents nod, each too afraid to speak. “Well, I certainly thought as much! Get your baskets ready, kiddies!” At his command, the children pick up their baskets. Some baskets are wicker, fraying and pulling themselves to pieces, while others’ are plastic and covered with faded decorations; some have handles, while some do not, having to be clasped close to the chest. The one thing in common to each and every basket is the white-knuckled grasp of the children holding them, waiting for the voice to speak again.

“And,” it says, with abundant relish, “Begin!” Slowly, the children spill into the woods, what little sunlight there is swallowed up in a netting of dark, dead foliage. A large group of the children, those who have never been on the hunt before, cut straight ahead, clumping together for safety, for they’ve heard of the terrible creatures that infest this place and rend flesh from bone.

The older children, splitting off alone into their own chosen directions, know that there are no such creatures. Nothing would want to live here.

Not to say that there is no danger, of course. Every year, fewer children come out than have gone in, the field outside emptying until there remain only those few parents who wait, and wait, and wait, and will never bring themselves to stop waiting.

There is the mire, which too many children fail to realize they’ve entered until they’ve forgotten the way they’ve come. There is the pit, which the older children stay away from, so that they do not have to hear the cries and the pleas of those who have fallen in. There is the lake, which means they’ve gone too far.

There are many ways to become lost in the woods. There are fewer ways to be found.

Still, despite the many dangers, the older children know that the greatest danger comes from those others on the hunt. Most everyone keeps to themselves, and true disputes are rare, but they are still avoided at all possible cost. Unmatched is the rage of a child who sees another’s full basket while their own remains empty, or who is pushed and drops what little they have.

Blood can be spilled. Worse, the prizes can be damaged. The children search for hours, grabbing at everything they find, desperation growing as success becomes rarer and rarer. Some even begin to claw at the dirt, sure that something might have been buried, the older children sadly shaking their heads as they pass by.

Some forgo their search, instead succumbing to curiosity and seeking the source of the voice, that voice that commands them to perform these tasks, that cheers them on as they go about their way, and that punishes those few foolish enough not to take part in the hunt.

They always find nothing, which is likely for the best. The other children know what their parents have told them, and they know that they do not ever want to find the master of this hunt.

Eventually, the game comes to a close. “Alright, kiddies!” the voice croons, from everywhere at once, “It’s time to wind up and wind down! Everyone back to the start!”

The children, all at once, look at their baskets, and then begin heading toward what they hope should be the exit. Some curse and cry, having just found a whole nest’s worth of goods, one or two daring to snatch a few more morsels before leaving.

On occasion, they are forgiven for such a transgression. On occasion. The children find their way back out of the woods, wordlessly met by those black-masked, black-robed sentries, who guide them back to their parents for the counting.

One-by-one, the children set their baskets down and step away, allowing the black-garbed men to assess their findings. No words are exchanged as they perform their inspections, slowly turning each egg over in their hands, dusting it off, smelling it, treating it like a prize specimen before setting it back in the basket.

Eventually, the children get back their baskets, allowed to leave with their overjoyed parents and be assured of a reasonable bounty to last the next year. The next child will then come up, and their basket will be inspected, and the cycle will repeat, again and again.

And then it will break. Sooner or later, one of the men picks up an egg and hesitates, weighing it carefully in his hands. Then he roughly tears at it, removing layers of dust, and dirt, and old flesh, until the sickly-colored shell falls away to reveal a gleaming inside.

Everyone sees it. After what feels like an age of silence, a mother and father begin to scream, rushing forward in delirious protest.

An outburst that would not be forgiven in any other context, save this. Even the black ones, as they hold back the parents, know what a shock this can be.

Monica Peters looks back at her parents, her blood turning to ice as realization comes at her in waves. She has always seen this occur, grieved along with all the rest of them, never once believed that it would happen to her.

Yet, she had found it. It was still there, in the man’s hand. She looks up to see him staring at her from behind an expressionless mask, pointing into the forest with a silent command. She considers that she could run. She then remembers that, no, she cannot. Monica gives a final look toward her parents, whispers a goodbye. As her father faints, and her mother wails in despair, they do not hear her.

Monica turns back to the woods, and she steps forward, guided by an instinct that she does not recognize. Her feet follow a path that she has never known, never tried, but that she is certain is the correct way.

After hours of walking, dirt caked between her toes and her soles beginning to blister, she finds a house. It’s a humble piece of work, a single story with carved-out windows, a dull, orange glow shining out toward her. She steps toward the door and, after the briefest moment of hesitation, she finds the courage to knock.

The door pushes inward at her touch, a silent invitation. Monica steps past the threshold, gazing about the humbly-furnished abode, looking for he who has summoned her.

“Monica!” comes the voice, that voice, “Monica, Monica, my little Monica!” There is a melody to the voice, more so than usual, an uncomfortable joyousness in its timbre. She looks about the room again, unable to find its source, only to feel something soft and warm on her shoulder.

Monica instinctively turns and jumps away in terror, muffling a shriek. Even as she recoils, she knows that this is who she has been made to seek, that this is the voice they fear, the master of their hunt.

He’s bigger than she thought he’d be, white ears bending over his face as he smiles at her. She cannot count the teeth in his smile.

“I thought that was you!” he says, giddily hopping in place as he claps to himself, “You know, don’t tell those other kids, but I knew that you would win this year! I knew it, I knew it, I knew it, I knew it!”

Monica says nothing, hugging herself and trying to make her legs stop shaking. He notices, but says nothing, too enraptured to ruin the moment with pedantry.

“Your parents must be so proud of you!” he coos, green eyes glinting in firelight. Receiving no reply, he leans in, his all-too-wide smile growing even wider. “Aren’t they?”

Monica nods, finds her voice to say, “Y-yes, sir. Very proud.” “Oh, I’ll bet! But, come, come!” He hops past her, beckoning with one hand. “We must catch up! I’ve made carrot cake!”

Monica, after one more fruitless glance at the front door, follows him into his sitting room, drinking his tea and eating his cake as he speaks, as he tells her so many things that she’s always wondered about but never known for certain.

His name is Peter, she learns. He tells her about the history of the hunt, how boring it had once been, but how much better he’s made it. He describes to her the history of the hunt, how the faith of one god had started with its tradition, then claimed the tradition and name of another god for its own, but that that didn’t matter, as he looked forward to surpassing them both. He tells her that this hunt has been going on for ages, ages, much longer than she had ever thought, in those times she could be brought to think on it.

Monica learns all these things, and more, before the time comes. Eventually, he takes her up in his arms and sings to her.

It is the first song she’s ever heard. Even so terrified, Monica feels herself begin to weep, crying shamefully as he lifts her toward his mouth.

He kisses her once on the forehead, then opens wide. As she is brought closer and closer in, Monica sees it through the tears in her eyes. After so many years of wondering, Monica sees what happens to the other children.

As he closes his mouth and the light fades away behind her, Monica sees all the other children who have ever found the golden egg.